Blackie Sherrod inspried Dan Jenkins, Bud Shrake, and everybody who ever read him.

"There have been about as many imitation Sherrods as there are sportswriters who drink," wrote someone in D, a magazine about his hometown of Dallas, in 1986,

William Forrest Sherrod (pronounced SHERR-uhd, not Sheh-RODD) was born on November 9, 1919 on a farm outside Belton, Texas. He later said that he read every book in Belton's library. We're talking about a small town in Texas -- in the 1920s and '30s, no less -- so that may not be as much of an accomplishment as you might think.

He attended Baylor University in Waco, then transferred to Howard Payne University in Brownwood, Texas, graduating in 1941. A football injury there ended his athletic career. It was there that his dark hair and complexion, supposedly a result of Cherokee blood, earned him the nickname Blackie. He didn't like it, but a later editor told him that "Blackie" would stand out on a byline more than "William," "Bill" or "Billy" would.

He served in the U.S. Navy during World War II, and was hired thereafter by the Temple Telegram. He soon moved on to the Fort Worth Press, and quickly became its sports editor. Jenkins and Shrake both wrote for him.

Jenkins once told of how he worked all night on his first story for the Press. He presented it to Sherrod, who read the first paragraph, and told him, "Don't ever write a morning lead for an afternoon newspaper, dumbass."

Can you imagine anyone saying that to a young reporter today? Of course not. Not because it's mean, but because there are no more afternoon newspapers.

In 1958, he was hired by the Dallas Times Herald. In spite of his being a sportswriter, they sent him to cover the 1960 Democratic Convention in Los Angeles. John F. Kennedy was nominated for President. When Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in 1963, Sherrod was the main rewrite man for the Times Herald's coverage. They also sent him to the space center named for JFK at Cape Canaveral, Florida, to cover Apollo 11 in 1969.

Following the 1963 National Championship won by the University of Texas Longhorns, Sherrod collaborated with their head coach on a book, Darrell Royal Talks Football.

In the 1967, '68 and '69 seasons, he was the color analyst on Dallas Cowboys games on KLIF radio, with Bill Mercer doing play-by-play. He quit just as the Cowboys started reaching Super Bowls, but he was one of the few writers in Texas to be openly critical of, if not "America's Team" as they began calling themselves in 1978, then certainly the most popular sports team in Texas. (After all, a big chunk of the State hates the Longhorns, but even Houston Oiler fans, in another conference, didn't particularly hate the Cowboys then. It's different with today's Houston Texans fans.)

He knew the Cowboys' fans were just short of worshipful, and he tended to refer to them in his columns as "Your Heroes" -- Capital Y, Capital H. While he liked head coach Tom Landry, he liked to call him "Mount Landry," as if his face and his famed hat were already on Mount Rushmore.

About the legendary Baltimore Colts quarterback Johnny Unitas: "He is a day laborer who somehow fell into fame on his way to work and it impresses him not a whit." Those words not only work, they have the added advantage of being true. (Disclaimer: I'm currently reading a biography of Unitas, hence last night's post examining how the Pittsburgh Steelers could have let him go.)

About Roger Staubach, the Cowboy quarterback known as "Captain America," who concluded a bad game with a game-winning drive: "Like putting a cherry on a glass of buttermilk."

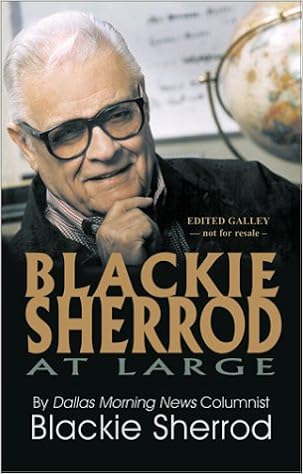

In 1985, he moved to the Dallas Morning News. In 1988, they collected his columns in The Blackie Sherrod Collection, with an introduction by Dan Jenkins, who, I suppose, now succeeds him as the great Texas sportswriter. (Fans of Mickey Herskowitz may feel free to disagree.) In 2003, another collection appeared, Blackie Sherrod At Large.

He married twice. The 1st marriage ended in divorce. He married Joyce Wilson in 1979, and she is his only known survivor.

After years of Alzheimer's disease, and his health further compromised by 2 recent falls at home (always a danger to elderly people), Blackie Sherrod died on April 28 at his home in Dallas. He was 96 years old.

For its obituary, The New York Times had a headline describing him as a "Texan Who Wrote About Sports With an Informed Swagger."

Aside from the part about being from Texas (unless you actually are from Texas), isn't that what any sportswriter should inspire to do with his or her writing?

UPDATE: I can't find any reference to a final resting place for him.

No comments:

Post a Comment